In the early 1970’s, New York City (still recoiling from the social upheaval of the previous decade) was struggling with a wave of deaths relating to heroin. This opioid epidemic of the late 20th century, familiar to a 21st-century audience as similar crises different face, serves as a backdrop for Richard Vetere’s play Black & White City Blues, playing at the American Theatre of Actors. It looks at addiction and how it impacts the life of its protagonist and his friends and family. In many ways it’s successful at presenting a look at that issue at that period of time in the city, and examining the different ways these people have ended up where they are. At times, however, it feels a bit bogged down as it repeatedly hits the nail on the head.

Subtitled with “A Junkie’s Struggle in a Decaying NYC, 1971”, Black & White City Blues follows Little Guy (Joseph Monseur) in the weeks following the death of his brother, John John (Sam Cruz). Guy struggles with his addiction, and tries to set up a deal with his friend Bobby (Jake Minter) to sell a large load of various drugs to a notorious dealer named Piranha (Riyadh Rollins) so that he can have enough money to get himself and his girlfriend Delilah (Amber Brookes) out of New York to somewhere they can start fresh.

Ultimately, the linear plot isn’t the main focus of the script. Much of the staging and the writing in some of the scenes (particularly noticeable in a family dinner scene at Guy’s house and a scene where he’s in a hospital receiving methadone treatment coming down from heroin) add a disjointed quality to the play. It focuses yes on plot points but also largely on thematic conversations. Questions of fate, of how or if we are able to change ourselves and take our lives in a different direction, of grief and trauma. Vetere writes poetically on these subjects. The biggest downside to this is that with the same sort of music underscoring multiple scenes in a row with these sorts of deliberations, there are too many places one after the other where the show feels like it is trying hard to hammer home an emotional point. That ultimately weakens the later moments of the play when the audience has been exposed to so much in one go.

The play also crams a lot of details into a 90 minute run time. This isn’t necessarily bad and it’s not overloaded, but it does mean a lot of things feel breezed past quickly. One character tries heroin for the first time, and the next time we see him he’s pretty desperately asking to score a bag and it’s noted he’s become quite big on getting high. Delilah’s abusive father is mentioned a handful of times, including the fact he died two years ago, but it seems to be told to the audience rather bluntly over the head than done much with (though yes it informs many of Delilah’s fears and behaviors). Occasionally, subtly has to give way to efficiency.

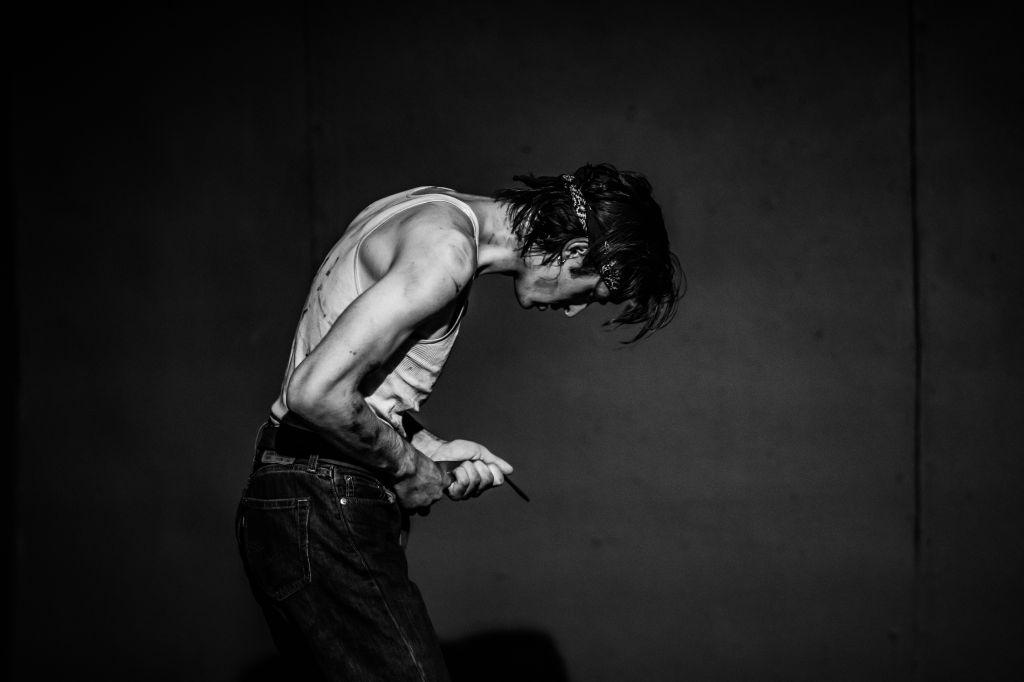

Monseur leads the cast brilliantly as Guy, in some scenes giving cool determination and in others desperation and a clawing grip at what he considers his sanity. Some of his strongest scenes are with Kevin Leonard as his drug counselor, Mr. Wellman. The two have a good rapport on stage, and Leonard’s performance is strongly grounded. Each member of the cast delivers a strong performance, most delivering beautifully written stories or monologues with clear precision.

Brookes also serves as the piece’s director. She crafts some incredibly engaging stage images and makes great use of the space to create distinct playing areas. The piece has a solid overarching vision. The costumes and makeup do a fantastic job creating each character, and Jake Smith has created a solid lighting design that shapes the space well. All of this helps tremendously to create the world with a more minimal set.

Black & White City Blues has a good heart with what it aims to achieve. It wants to look at addiction and circumstance in a meaningful way, and these are topics worth exploring. They’re dealt with in this show with a good amount of sensitivity and care. And the backdrop of the city in the 70’s in a fascinating era to look at. But at times, despite strong pieces in play, the piece falls slightly into the heavy handed and can’t quite hit the mark. It’s a solid piece, a good play, with many clearly skilled artists contributing to it. For myself personally, I think there are notes that just didn’t fully resonate. At the end of the day, this seems like a piece that can strongly fall into a matter of personal preferences for any given audience member, and I applaud it for its ambitions.